Park Slope’s Hidden History: The Survivance of the Lenape

Honoring and celebrating 400 years of Lenape survival and resistance

Morgan DeMartis is a lifelong New Yorker with a passion for uncovering pieces of New York City history that are often hidden in plain sight. If you have a tip or story that you’d like Morgan to research, contact info@parkslopeliving.com or submit a tip here. Follow Morgan on Substack for more.

Author’s Note: In this article I use the word “Lenape” to refer to the Indigenous people of Lenapehoking, though different tribes use different names. “Lenape” comes from the Unami language, “Lunáapeew” comes from the Munsee language, and other words like “Lenni-Lenape” and “Delaware” are also used.

When visiting cultural institutions throughout New York City today you might encounter some form of a living land acknowledgement that honors the Lenape. As current residents of this city we must ensure that we are all aware of the full history of the Lenape, the true Native New Yorkers. Before there was New York City, there was, and is, Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Lenape people. It is our shared responsibility to learn about their stories and struggles and uplift those who continue fighting for recognition, advocacy, and social justice.

Lenape means “human beings” or, “the ones who came from thought.” They are the first inhabitants to live in Lenapehoking, which encompasses all of what is known as Brooklyn today. In fact, all of New York City as well as the Hudson Valley, New Jersey, parts of Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Delaware exist on Lenapehoking. The Lenape thrived on this vast expansion of land for at least 10,000 years before European arrival and by the 1600s there were around 20,000 people living here.

Storytelling is an integral part of Lenape culture with many folktales passed down throughout generations. The Lenape creation story begins with a great turtle who rose from the water and became dry. The turtle symbolizes the Earth, and for that reason the Lenape refer to the land as “Turtle Island.”

There are three main Lenape clans that each have their own unique dialect: Munsee (Wolf), Unami (Turtle), and Unalaxtako (Turkey). These dialects were the first languages spoken here in modern-day New York. Lenape are also referred to as “Delaware,” though this is not a Lenape word. It is derived from the third Lord de la Warr who governed Jamestown, Virginia and whose name was later given to the Delaware river. The Lenape who lived along the river were then referred to as the “Delaware,” and many still identify with the term today.

The Lenape Talking Dictionary offers learners the chance to read and hear Lenape living languages. For example, “Park Slope” translates to, wëlakamike: “pretty place (such as a park)” pënaonkòhchunk: “place where the land slopes downhill.”

Nulelìntàmuhëna èli paèkw Lenapehoking. Kulawsihëmo enta ahpièkw. (Umami Language)

Nooleelundamuneen eeli payeekw. Lunaapeewahkiing. Wulaawsiikw neeli apiiyeekw. (Munsee Language)

We are glad because you people come to Lenapehoking. Live well while you are here. (English Language)

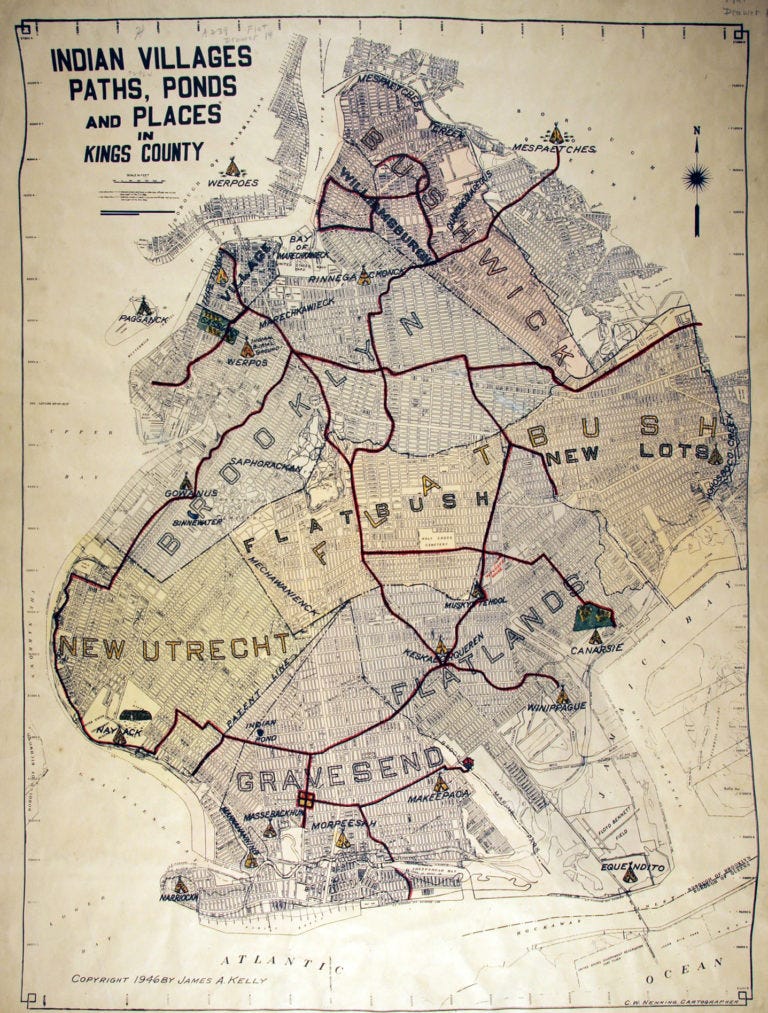

Lenapehoking contained many villages with at least 25 established in Brooklyn. The village of Marechkawick was the closest to what is now Park Slope. In the 1630s there were several hundred Lenape who lived in Marechkawick under Chief Seysey. Like other Lenape villages, the community lived off of the land which provided everything that they needed to survive and thrive.

The lineage of each clan member was traced through the matrilineal line. A clan’s lands and dwellings were managed by women leaders, though no land was ever “owned” by one tribe as there was no concept of land ownership. Family is very important to the Lenape, and extended families lived together in large homes called wikwama or wigwams.

Lenape names like Canarsee, Mosholu, Maspeth, Rockaway, and Gowanus are still used throughout the city today. The Éenda-Lŭnaapeewáhkiing Collective is currently doing research on confirming the original Lenape names for places like Gowanus and Rockaway, which most likely evolved from the Lenape word for “a sandy place.”

Lenape in Marechkawick thrived on one of the best food sources in Lenapehoking: Gowanus oysters. They would process and dry oysters in late summer and early fall to enjoy in the winter. Shells from nearby waterways were used by Lenape artisans to create wampum, which hold multiple functions in Lenape culture. Wampum were used to make agreements and solidify treaties, to record history, to adorn clothing, and to trade goods with other Indigenous communities.

Lenape spirituality is rooted in a deep connection with nature. Like other villages, Marechkawick had a Big House (Xinkwikaon), which functioned as a center of government and religion. Every four years the village would gather with their neighbors to discuss governance and visions of the future.

The Big House ceremony or rite lasts for twelve days during the harvest season, with each day having a universal principle to reflect upon. During Big House ceremonies the community prays together, using tobacco smoke as an offering during worship. Tobacco is sacred and was also used when planting or harvesting crops, when an animal was killed for food, to give thanks before meals, or when beginning a journey. The Big House ceremony created space for thanksgiving and celebration that reaffirms the Lenape’s connection to the land and their ancestors.

~~ In honor of Native American Heritage Month please enjoy this free article. To read more local history, subscribe to Park Slope Pulse ~~

The Lenape maintained highly sophisticated agricultural practices. Lenape farmers grew the “Three Sisters:” corn, beans and squash. Agricultural exchanges of plums, wild cherries, crabbapples, persimmons, and peaches took place throughout Lenapehoking. Fruits and vegetables were not only consumed, but used for medicinal purposes. In an article for NYC Tourism, Joe Baker, the Executive Director of the Lenape Center, remarks:

“It was in many ways a paradise. Everything one needed to live and thrive was provided here—in the richness of the forest, and the rivers and sea. It wasn’t a desolate, deserted land. It was very populated and very desirable.”

Unfortunately, Europeans realized what the Lenape had known for thousands of years: the land was prosperous which meant that for them it could become profitable. The Voices of Lunáapeew/Lenape exhibit at Lefferts Historic House features members of the Éenda-Lŭnaapeewáhkiing Collective who told the story of a vision that their ancestors had before European contact. The prophecy stated that the “salty people” would arrive from across the sea as either friends or enemies.

This vision came true when the Dutch arrived in 1624. They were severely ill, and had it not been for the friendship of the Lenape, they would not have survived. Because the Lenape were the first on Turtle Island to make contact with the “salty people” they are referred to by other nations as the “grandfathers” because they were the first ones targeted by colonization.

The Dutch quickly set up the Dutch West India Company, a corporation that was modeled on its eastern counterpart that exploited the sacred lands of Lenapehoking and its people. Soon, 95 percent of the woodlands in the Northeast were cut down and the timber was shipped and sold across the Atlantic. The loss of trees and the habitats that they housed created an environmental disaster in Lenapehoking. Neither the Earth nor the Lenape people were spared from the devastating effects of European colonization.

On February 25th 1643, Dutch soldiers, under cover of night, attacked a Lenape village at Pavonia in what is now New Jersey. The Pavonia Massacre was one of the first major acts of violence against the Lenape that preempted Kieft’s War, which lasted for almost three years and led to more massacres and more land seizures.

Kieft’s War ravaged through modern-day Brooklyn and the Dutch West India Company seized what is now Flatbush by force in 1645. Though the war ended that same year, the Lenape continued to suffer as they were pushed further out of their homeland. Years of destruction through land theft, exposure to foreign disease, decimation of crops, and brutal massacres led to the Lenape suffering a genocide at the hands of the Dutch and in 1664, the British.

It is important here to dispel a prolonged and horribly incorrect myth: that the Dutch “purchased” Lenapehoking from its people. As mentioned, the Lenape had no concept of land “ownership.” The Lenape likely viewed the “sale” of their land as a deal to share the land with the Dutch. In his book The Grandfathers Speak: Native American Folk Tales of the Lenapé People, Lenape Chief Hìtakonanulaxk writes,

“Our concept of land is that it is not a thing to be possessed, but rather something sacred and alive. We have a saying, “We do not own the land, we are of the land, we belong to it.” We call the Earth Kukna, our mother. All life comes from the earth, she nourishes us, carries all life and gives us a place to put our feet.”

By 1700 the Lenape population was reduced by 85 percent. Those who survived were forced by the British and later the United States government to migrate long distances, displaced further and further west by unjust treaties and armed colonizers. The Lenape who were forced into this migration are referred to as, “Those that ran.” They understood how important it was to preserve their cultural practices, songs, and knowledge as they were forced to leave their homelands.

At the Voices of Lunáapeew/Lenape exhibit, one of the members of the EL Collective asks: “What would you do if it was your home? If it was your family who were being removed?” Today the Lenape can be found all throughout Turtle Island in places like Oklahoma, Wisconsin, California, and Canada.

Though the Lenape suffered greatly for centuries through genocide and forced removal, they are resilient survivors who continue to preserve and celebrate their culture. Organizations like the Lenape Center and the EL Collective curate educational programming and events throughout Turtle Island which allows the Lenape to be the ones to share their own history.

These organizations are working hard to dispel yet another myth: that the Lenape no longer exist. While the number of Lenape who live in New York City today numbers five individuals according to the Lenape Center, many tribal members have worked hard to return to their homeland.

In the 1970s and 1980s Nora Thompson Deane, a Lenape artist, teacher, and herbalist, made multiple journeys from Oklahoma to Lenapehoking. She worked hard to tell the story of her people and became a mentor for many, including Joe Baker. She even secured a meeting with former NYC mayor Ed Koch but sadly he never showed up.

“Though we were displaced from our homeland, our ancestors remain here. Our culture continues to reverberate within the natural elements of the territory, in the wind, the air, the water, the rocks. We exist eternally in our homeland.” - Joe Baker

In 2021 the Lenape Center created the seed rematriation project, which finally returned Lenape crops to their native soil after hundreds of years. Farm Hub partnered with the organization to cultivate these indigenous crops in the Hudson Valley. And just this September Prospect Park hosted the Second United Lenape/Lunáapeew Nations Pow Wow, which was the first Pow Wow held in Prospect Park since 1972 and the second ever Lenape Pow Wow to take place within New York City. Check out this video for a glimpse of this year’s Pow-wow:

This article is but a brief overview of Lenape history and their survivance throughout Turtle Island. To learn more and to continue celebrating Lenape traditions and culture please explore these other resources:

The Eelunaapéewi Ehaptoonáakanal: Voices of Lunáapeew/ Lenape exhibit at Lefferts Historic House is on view until November 30th.

The Old Stone House has a section on the Lenape in their permanent interactive exhibit.

Virtually explore the Lenapehoking Exhibit by the Lenape Center in collaboration with the Brooklyn Public Library.

Explore the Lenape Talking Dictionary.

Learn more about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) Crisis.

Click here to listen to members of the EL Collective as they share their voices and stories in partnership with the Amsterdam Museum.

Reading list:

Lenape Children’s Books list curated by the BPL

Lenapehoking: An Anthology: A project of the Lenape Center & Brooklyn Public Library

The Grandfathers Speak: Native American Folk Tales of the Lenapé People by Hìtakonanulaxk

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History by Ned Blackhawk

Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West by Ned Blackhawk

Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society before William Penn by Jean R Soderlund

Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence edited by Gerald Vizenor